FDM 3D Printing Technology | Fast, Functional Layered Parts

FDM additive manufacturing for rapid, reliable 3D printing of functional parts, prototypes and fixtures with strong material options and efficient workflows

A Manufacturing Method That Changed the Rules

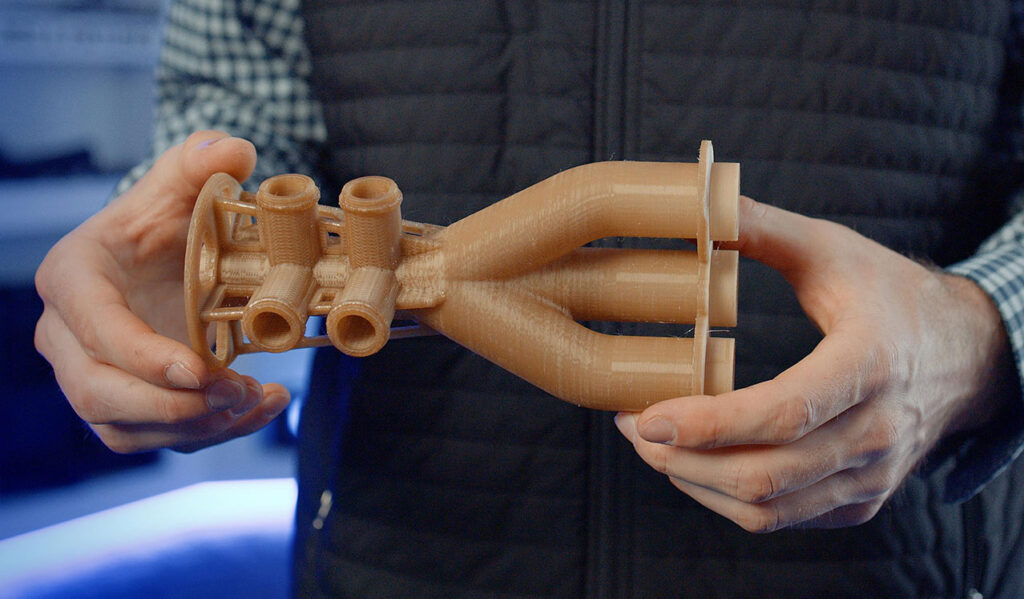

Fused Deposition Modelling, commonly referred to as FDM, is one of those technologies that looks deceptively simple on the surface yet quietly underpins a very large proportion of modern additive manufacturing. At its core, FDM is a process where a thermoplastic filament is heated, extruded through a nozzle, and deposited layer by layer to form a solid object. That description alone does not do it justice. What makes FDM unique is not merely how it builds parts, but how it changes the economics, timelines, and accessibility of manufacturing altogether. Unlike traditional subtractive methods, where material is removed to reveal a shape, or injection moulding, where tooling dictates what is possible, FDM allows parts to be created directly from a digital model with minimal setup, minimal waste, and near-instant iteration. This fundamentally alters how designers, engineers, and businesses approach problem-solving. Instead of committing thousands of pounds and months of lead time to tooling, FDM enables a pragmatic, responsive approach: design, test, refine, and deploy, all within days rather than quarters.

What truly sets FDM apart is its balance between capability and practicality. It is not trying to be everything at once. It does not claim mirror-smooth surfaces out of the machine or micron-level tolerances without post-processing. Instead, it focuses on strength, functionality, adaptability, and cost control. The materials used—ABS, PETG, PLA, Nylon, carbon-fibre-reinforced polymers—are proven engineering plastics that already exist in countless industrial and domestic products. FDM simply provides a different route to shaping them. This means parts produced via FDM are not experimental novelties; they are real-world components capable of withstanding mechanical loads, repeated use, and environmental exposure when specified correctly. From brackets and housings to jigs, fixtures, and legacy spares, FDM excels precisely because it aligns with how engineers think: fit for purpose, not ornamental excess.

Another defining characteristic of FDM is its scalability in the small. Traditional manufacturing methods become economical only when volumes rise. FDM, by contrast, thrives in low-volume, bespoke, and on-demand scenarios. This is where it delivers its greatest value. When a single component fails on a machine, when a legacy part is no longer available, or when a prototype needs to be tested in situ rather than on paper, FDM steps in as a practical solution. It removes the false choice between “too expensive” and “not possible.” Instead, it offers a third path: make exactly what is needed, in the quantity required, when it is required. That flexibility is not a side benefit; it is the defining feature of the technology.

FDM also introduces a level of design freedom that conventional processes actively discourage. Internal channels, complex geometries, integrated fasteners, and weight-optimised structures are not only possible but often trivial to produce. Engineers are no longer forced to simplify designs purely for manufacturability. Instead, manufacturability adapts to the design. This shift has subtle but far-reaching consequences. Products can be lighter without sacrificing strength, assemblies can be reduced to fewer parts, and failure points can be engineered out rather than worked around. Over time, this leads to better products, not just cheaper ones. That is a distinction often overlooked when people focus solely on unit cost rather than lifecycle value.

Finally, FDM is unique in how it democratizes manufacturing capability. The same core technology scales from desktop systems to industrial machines capable of producing large, structurally robust parts. The learning curve is approachable, yet mastery rewards experience and material understanding. This combination has allowed FDM to move beyond novelty and firmly into the realm of serious manufacturing. It is no longer a question of whether FDM belongs in professional environments; the real question is why it would be excluded.

- Brackets, housings, mounts, covers and functional prototypes

- Jigs and fixtures for workshop or manufacturing use

- Short-run parts where injection moulding isn’t viable

Why Fused Deposition Modelling Matters in Modern Manufacturing

The importance of FDM lies not in replacing every other manufacturing method, but in filling the gaps those methods leave behind. Traditional manufacturing is excellent at repetition and volume, but it struggles with change. FDM thrives on change. That alone makes it indispensable in a world where products evolve rapidly, supply chains are fragile, and downtime carries real financial consequences. When a business can design and produce a functional component internally or through a local service provider, it reduces reliance on distant suppliers and opaque lead times. That resilience is not theoretical; it is measurable in reduced downtime, faster repairs, and lower overall risk.

From an economic standpoint, FDM changes the cost curve entirely. There is no tooling cost in the traditional sense. The investment shifts from fixed upfront expenditure to variable, project-based spending. This is particularly valuable for small and medium-sized enterprises, maintenance departments, and specialist operators who simply do not have the volume to justify moulds or dies. With FDM, the first part costs roughly the same as the tenth. That predictability allows better budgeting and more informed decision-making. It also encourages experimentation, because the penalty for getting something slightly wrong is minimal compared to traditional manufacturing errors.

There is also a strong environmental argument in favour of FDM when used appropriately. Additive manufacturing produces far less waste than subtractive methods, and material usage can be optimised through infill control and geometry design. Parts can be produced locally, reducing transportation emissions and packaging waste. Moreover, the ability to repair or replace a single failed component rather than discarding an entire assembly aligns closely with principles of sustainability and circular manufacturing. FDM does not just make things cheaper; it often makes them more responsible.

Another reason FDM matters is its role in bridging the gap between design and reality. CAD models are invaluable, but they remain theoretical until tested in the real world. FDM allows those designs to be validated physically, under real loads and conditions, before committing to large-scale production. This reduces costly errors and improves final product quality. It also fosters closer collaboration between designers, engineers, and end users, because feedback can be incorporated quickly rather than deferred to the next production cycle.

Crucially, FDM empowers problem-solving at the point of need. Instead of waiting for solutions to arrive, teams can create them. That cultural shift—from dependency to capability—is perhaps the most significant contribution FDM makes to modern manufacturing.

How FDM Works in Practice and Why That Matters

In practical terms, FDM begins with a digital 3D model, typically created in CAD software. That model is then sliced into layers, each defining the path the printer will follow. A filament is heated to its melting point and extruded through a nozzle, depositing material precisely where required. Layer by layer, the part takes shape. This process may sound straightforward, but its effectiveness depends heavily on material choice, print orientation, infill density, layer height, and thermal management. These variables are not obstacles; they are tools. When understood and applied correctly, they allow the strength, weight, and performance of a part to be tuned to its intended use.

One of the most important aspects of FDM is infill. Unlike solid moulded parts, FDM components can be produced with internal structures that balance strength and material usage. A purely decorative part might require minimal infill, while a load-bearing component may be printed at or near 100% infill for maximum strength. This flexibility allows cost and performance to be aligned with real-world requirements rather than theoretical extremes. It also means conversations with clients are grounded in use cases rather than assumptions.

Material behaviour is equally critical. ABS offers toughness and heat resistance but degrades under prolonged UV exposure. PETG provides improved UV stability and a cleaner finish. Nylon excels in strength and wear resistance but demands precise printing conditions. FDM allows these materials to be deployed selectively, matching the properties of the plastic to the demands of the application. That is not experimentation; it is engineering judgment applied through a flexible manufacturing process.

Post-processing further extends what FDM can achieve. Sanding, priming, coating, and reinforcement can elevate a functional print into a finished component suitable for visible or demanding environments. This layered approach—print, refine, deploy—mirrors traditional manufacturing workflows but without their rigidity or cost barriers.

The Economic Benefits of FDM for Businesses and Industry

From a business perspective, FDM offers a compelling value proposition rooted in speed, flexibility, and cost efficiency. The ability to move from concept to physical part in a matter of hours or days transforms decision-making. Maintenance teams can respond to failures immediately rather than waiting weeks for spares. Product developers can test multiple iterations without inflating budgets. Small production runs become viable instead of being dismissed as uneconomical.

FDM also reduces risk. Because tooling is not required, designs can evolve without sunk-cost anxiety. If a part needs modification, the digital model is updated and reprinted. There is no obsolete mould, no wasted inventory, and no pressure to “make do” with a flawed design simply because it was expensive to produce. That agility has tangible financial benefits over time, even if the per-unit cost appears higher than mass production on paper.

Localised production is another economic advantage. By producing parts closer to where they are needed, businesses can shorten supply chains and reduce exposure to global disruptions. This is particularly relevant in sectors where uptime is critical and delays carry cascading costs. FDM supports a more resilient, decentralised manufacturing model that aligns with modern operational realities.

The Human and Practical Impact of FDM Adoption

Beyond balance sheets and technical specifications, FDM has a human impact that is often overlooked. It enables skilled tradespeople, engineers, and designers to apply their expertise directly to solving problems rather than navigating procurement bottlenecks. It encourages learning, adaptation, and ownership of outcomes. When people can see their ideas translated into physical objects quickly, engagement and innovation naturally increase.

For customers, FDM often represents the difference between compromise and resolution. Instead of being told a part is obsolete or unavailable, they are offered a solution tailored to their specific need. That builds trust and long-term relationships rather than transactional exchanges. In practical terms, it means machines stay running, projects move forward, and resources are used more intelligently.