Nylon 3D Printing Material UK | Tough & Wear‑Resistant Prints

Flexible and wear‑resistant nylon for engineering‑grade 3D printed parts with functional strength and extended service life.

What Makes Nylon Filament Fundamentally Different

Nylon filament sits firmly in the engineering-grade category of 3D printing materials, and it earns that position through a very specific combination of mechanical strength, flexibility, and long-term durability. Unlike common consumer materials such as PLA or even PETG, nylon is not brittle by nature. It is tough, impact-resistant, and capable of absorbing repeated stress cycles without cracking or snapping. This is the reason nylon has been used for decades in injection-moulded industrial parts long before desktop 3D printers were even a consideration. When brought into the additive manufacturing space, nylon changes what is realistically possible with printed components.

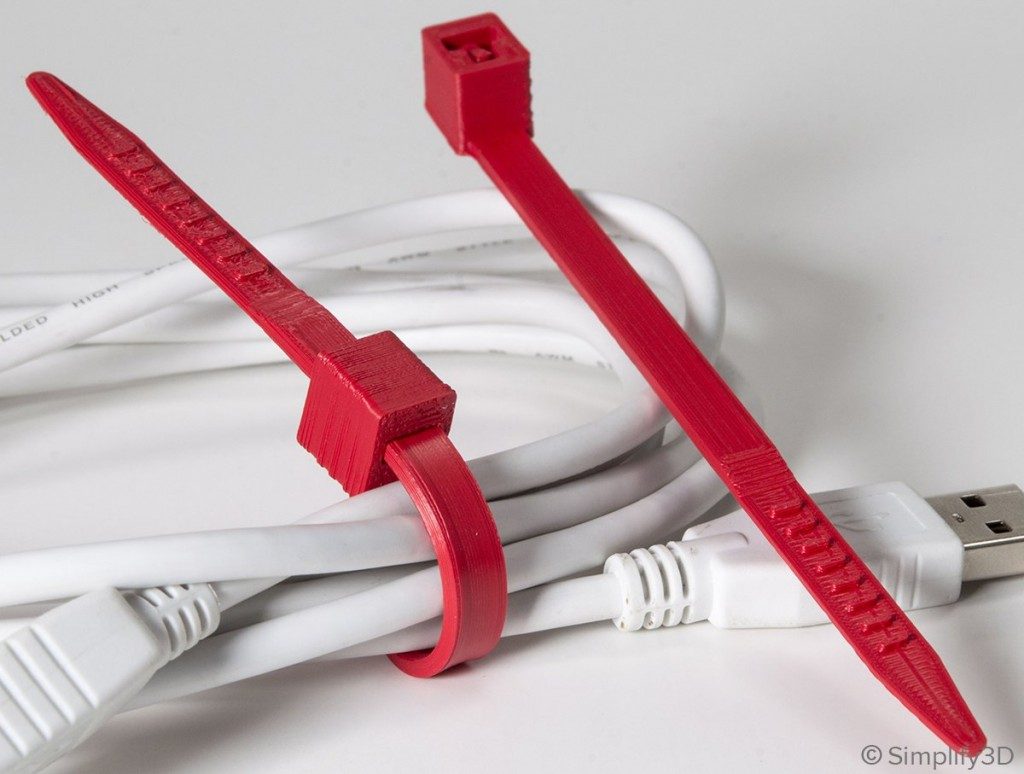

One of nylon’s defining characteristics is its molecular structure. It is a semi-crystalline polymer, which gives it a unique balance between rigidity and elasticity. In practical terms, this means a nylon part can flex slightly under load and then return to its original shape rather than failing catastrophically. That single property alone makes nylon ideal for clips, hinges, gears, bushings, snap-fit enclosures, and functional brackets—parts that would quickly fail if printed in stiffer but more brittle plastics.

Another key difference is abrasion resistance. Nylon handles friction extremely well. Where PLA would grind itself down and PETG would start to deform, nylon continues to perform. This makes it suitable for moving parts and mechanical interfaces where surfaces rub against each other repeatedly. In workshops, factories, marine environments, and transport applications, this resistance to wear translates directly into longer service life and fewer replacements.

However, nylon is not a “plug-and-play” filament. It demands more from both the printer and the operator. It requires higher extrusion temperatures, controlled cooling, and—most importantly—dry storage. Nylon is hygroscopic, meaning it absorbs moisture from the air. If printed wet, it will pop, hiss, string, and lose strength. When handled correctly, though, the payoff is substantial. A properly printed nylon part feels and behaves far closer to a traditionally manufactured component than most people expect from a 3D printer.

This is why nylon is often chosen not for prototypes, but for final-use parts. It bridges the gap between rapid manufacturing and industrial production, allowing small businesses, maintenance teams, and engineers to create parts that genuinely work in the real world—not just on a desk or a display shelf.

Why Nylon Is an Engineering Material, Not a Hobby Plastic

The reason nylon is classified as an engineering material has very little to do with marketing and everything to do with performance under real operating conditions. Engineering plastics are defined by their ability to handle mechanical load, temperature variation, vibration, and chemical exposure over extended periods of time. Nylon excels in all four areas when compared to entry-level filaments.

Mechanically, nylon offers high tensile strength combined with excellent elongation at break. This means it can withstand significant pulling forces before failure and can stretch under load rather than cracking instantly. In practical terms, this gives designers a safety margin. A nylon component will often show visible deformation before failure, providing warning rather than sudden breakage. This is critical in applications involving machinery, transport systems, and safety-related assemblies.

Thermally, nylon performs well in environments where PLA would soften and fail. While it does not match the extreme heat resistance of high-end polymers like PEEK, it comfortably operates in temperature ranges that cover the majority of industrial and commercial use cases. This includes engine bays, electrical housings, and equipment exposed to intermittent heat.

Chemically, nylon is resistant to oils, greases, fuels, and many solvents. This is one of the reasons it is widely used in automotive and marine industries. A 3D-printed nylon part exposed to lubricants or diesel vapour will maintain its integrity far better than most alternative filaments.

What truly elevates nylon, however, is its fatigue resistance. Repeated loading and unloading—bending, twisting, vibration—are where many plastics fail prematurely. Nylon thrives here. This makes it ideal for parts that are used daily, repeatedly, and under stress. When customers ask for something “that won’t just snap after a few months,” nylon is often the correct answer.

From a manufacturing perspective, nylon also enables low-volume production that would otherwise be economically impossible. Injection moulding tooling costs can easily reach thousands of pounds before a single part is produced. Nylon filament allows those same functional components to be manufactured directly, in small batches, with design changes implemented immediately rather than months later.

How 3D Printing Nylon Delivers Real-World Benefits

The real benefit of 3D printing nylon is not theoretical—it is practical, measurable, and financial. The ability to produce durable, functional parts on demand fundamentally changes how problems are solved. Instead of sourcing obsolete components, redesigning assemblies around unavailable parts, or committing to expensive tooling, nylon enables rapid, targeted solutions.

From a business standpoint, downtime is often more expensive than the part itself. When a machine is idle because of a broken clip, spacer, or gear, production halts. Nylon allows those parts to be recreated quickly, often stronger than the original. This is especially valuable in legacy systems where spare parts are no longer manufactured.

For engineers and designers, nylon offers design freedom. Features such as internal channels, complex geometries, and integrated fasteners can be printed directly rather than assembled from multiple components. This reduces failure points and simplifies maintenance. Because nylon supports high infill densities, parts can be tuned precisely for strength, flexibility, or weight depending on the application.

There is also a sustainability angle that should not be overlooked. Printing a nylon component locally reduces transport, packaging, and waste. Instead of ordering replacements from overseas suppliers, parts can be produced where they are needed, when they are needed. In many cases, only the damaged component needs replacing rather than an entire assembly.

For individuals and small businesses, nylon levels the playing field. Capabilities that once required industrial supply chains are now accessible with the right printer setup and material handling. This democratisation of manufacturing is not about novelty—it is about resilience, cost control, and independence.

The Technical Reality of Printing Nylon Correctly

Printing nylon successfully requires understanding its technical behaviour rather than treating it like a forgiving hobby filament. Extrusion temperatures typically range between 240°C and 280°C, depending on the specific nylon formulation (PA6, PA12, copolymers, or blends). A heated bed is essential, usually set between 70°C and 100°C, to ensure proper adhesion and reduce warping.

Enclosure is strongly recommended. Nylon shrinks as it cools, and uncontrolled temperature gradients can lead to warping or layer separation. A stable thermal environment ensures consistent layer bonding and dimensional accuracy.

Moisture control is non-negotiable. Nylon filament should be dried before printing, typically at 60–80°C for 6–12 hours, and ideally printed directly from a dry box. Wet nylon compromises layer adhesion, surface finish, and mechanical strength.

Infill selection plays a significant role in final performance. For load-bearing parts, infill levels of 60–100% are common. Wall thickness should be increased to distribute stress effectively. Layer height is often kept moderate to maximise layer bonding rather than surface detail.

When printed correctly, the resulting parts are dense, tough, and mechanically reliable. Poor setup produces weak, inconsistent components. This difference is why nylon has a reputation for being “difficult”—not because it is unreliable, but because it demands discipline and proper process control.

A Real-World Application: Functional Replacement Parts

A common real-world application for nylon filament is the replacement of discontinued or damaged mechanical components. Consider industrial control systems, transport infrastructure, or heritage machinery where plastic clips, spacers, or housings fail after decades of use. Original tooling no longer exists, and replacement assemblies may cost thousands.

Using nylon, a broken component can be reverse-engineered, redesigned to improve weak points, and produced in a matter of days. Features such as thicker stress points, reinforced ribs, and improved tolerances can be incorporated without increasing cost. The result is often a superior part compared to the original injection-moulded version.

In environments involving vibration—rail systems, marine equipment, automotive interiors—nylon’s fatigue resistance proves invaluable. Components continue to perform under repeated use, resisting cracking and wear. When required, post-processing techniques such as annealing or resin reinforcement can further enhance strength and longevity.

This is not theoretical manufacturing. These are working parts, installed, used daily, and expected to perform reliably. Nylon makes that possible without the financial barrier of traditional manufacturing.

FAQs

Is Nylon suitable for outdoor use?

It depends on UV exposure and heat. Tell us the environment and we’ll advise the best material.

Can you print Nylon for functional parts?

Yes. If you share the part purpose and any load/heat details, we’ll confirm the best settings and material choice.