ABS 3D Printing Material UK | Durable Plastic for Functional Parts

ABS 3D printing material — strong, impact‑resistant and ideal for functional parts, prototypes and industrial components with professional additive manufacturing

A Proven Engineering Plastic That Still Earns Its Place

ABS filament—Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene—is not a fashionable newcomer in the 3D-printing world, and that is precisely its strength. ABS has decades of industrial pedigree behind it. It is an engineering thermoplastic originally developed for impact resistance, dimensional stability, and toughness, and those properties translate directly into additive manufacturing when the material is handled correctly. Unlike softer or purely cosmetic filaments, ABS is designed to cope with stress, movement, and repeated mechanical loading. That is why it appears in automotive trim, consumer electronics housings, power-tool casings, and countless mechanical assemblies that people interact with daily, often without realising it.

From a molecular standpoint, ABS is a blend rather than a single polymer. Acrylonitrile provides chemical resistance and rigidity, butadiene contributes impact resistance and toughness, and styrene adds surface finish and processability. The balance of these components is what gives ABS its characteristic combination of strength and resilience. In practical terms, this means ABS can flex slightly under load without cracking, absorb impacts that would shatter more brittle plastics, and maintain its shape when subjected to moderate heat. These attributes make it far more than a “budget filament” when used correctly.

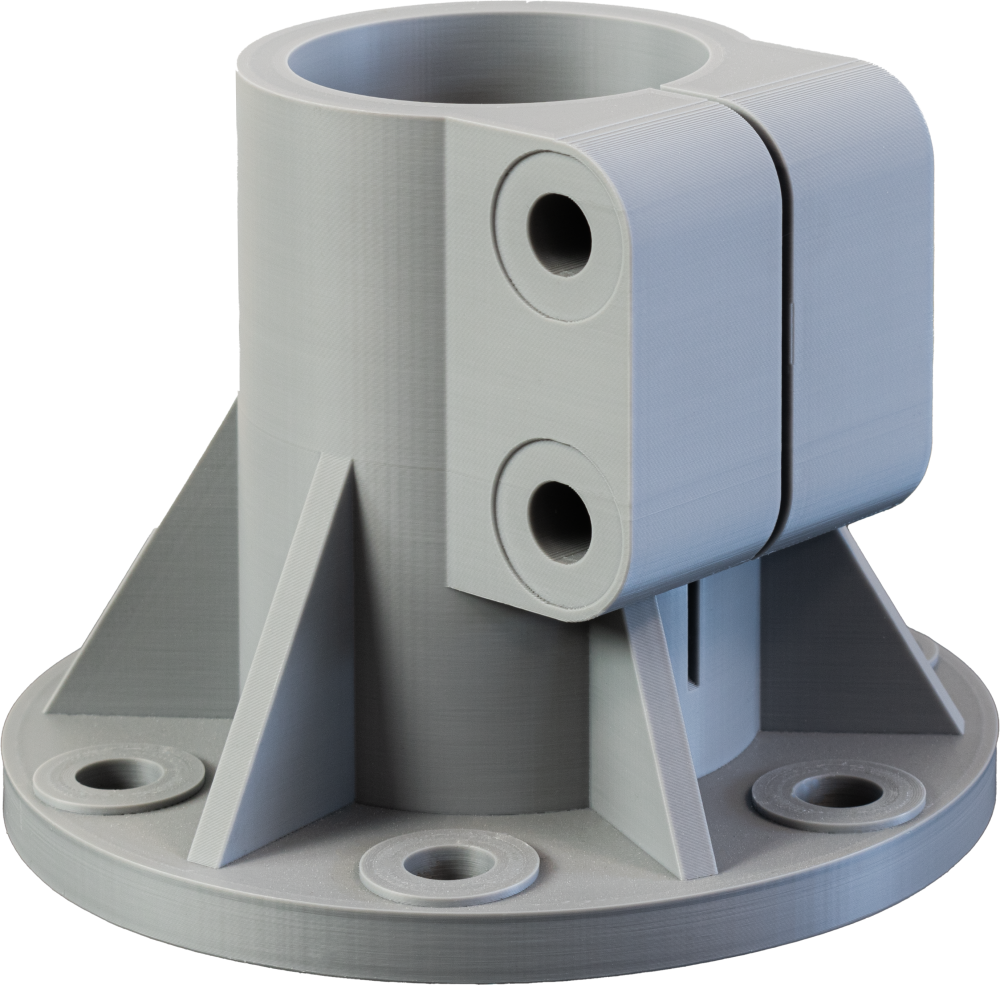

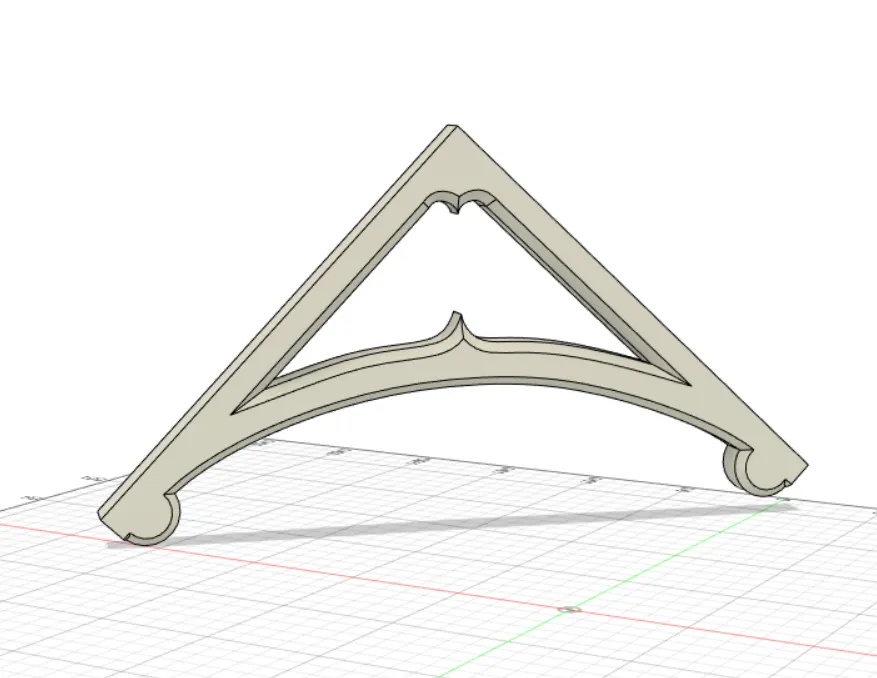

What sets ABS apart in 3D printing is its ability to produce functional parts rather than decorative ones. When printed with proper temperature control, adequate enclosure, and sensible infill strategy, ABS parts can be genuinely load-bearing. This is not theoretical strength; it is strength that translates into hinges, clips, brackets, mounts, and housings that are expected to work every day. ABS also responds well to post-processing, which further elevates it above many modern filaments. It can be sanded cleanly, chemically smoothed with acetone vapour, bonded with solvents, and even painted to a near-injection-moulded finish.

However, ABS demands respect. It is not forgiving of poor setup. Warping, shrinkage, and layer separation are common complaints from inexperienced users, not because ABS is flawed, but because it reveals weaknesses in printer control. Once those variables are managed—bed adhesion, controlled cooling, and thermal consistency—ABS becomes extremely predictable. In professional environments, predictability matters far more than novelty. That is why ABS remains a staple material in industrial and commercial additive manufacturing despite the explosion of alternative filaments.

- Brackets, housings, mounts and enclosures

- Functional prototypes that must be handled and tested

- Clips and parts where impact resistance matters

Why ABS Still Matters in a Crowded Filament Market

The modern filament market is saturated with blends, composites, and “enhanced” plastics promising easier printing or superior performance. Yet ABS continues to hold its ground because it occupies a critical middle space: it offers engineering-grade performance without the complexity or cost of high-end nylons or fibre-reinforced materials. This makes ABS uniquely valuable for short-run manufacturing, prototyping, and replacement parts where performance matters but budgets are realistic.

ABS excels where dimensional stability is required after printing. Once fully cooled and stress-relieved, ABS parts tend to remain stable over time, provided they are not exposed to excessive UV radiation. This stability is critical for parts that must align with existing components—snap-fit assemblies, sliding mechanisms, or mating surfaces. In contrast, some easier-to-print filaments can creep, deform, or fatigue under sustained load, leading to premature failure in real-world use.

Another reason ABS remains relevant is its thermal performance. With a glass transition temperature typically around 105 °C, ABS can operate safely in environments that would soften PLA and challenge PETG. This opens the door to applications near motors, electronics, or warm enclosures where heat buildup is unavoidable. For businesses producing functional components rather than display pieces, this thermal resilience is often non-negotiable.

There is also a manufacturing argument. ABS bridges the gap between 3D printing and traditional injection moulding. The same base material is used in both processes, meaning printed prototypes behave similarly to eventual moulded parts. This is invaluable when validating fit, function, and durability before committing to expensive tooling. For low-volume production, ABS 3D printing can bypass tooling entirely, delivering parts at a fraction of the cost and lead time.

In short, ABS is not outdated—it is established. In engineering, established materials are trusted because their limitations are known and manageable. ABS does not pretend to be UV-stable, flexible, or decorative by default. What it does offer is strength, consistency, and industrial relevance. That clarity is exactly why it continues to be specified for serious applications.

How ABS Performs in Real-World 3D Printing

Printing ABS successfully is about control rather than compromise. ABS typically prints at nozzle temperatures between 230 °C and 260 °C, with a heated bed around 90 °C to 110 °C. These temperatures are not arbitrary; they ensure proper layer fusion and minimise internal stresses that cause warping. A fully enclosed build chamber is strongly recommended, as ABS is sensitive to rapid temperature changes during printing.

Layer adhesion is one of ABS’s strengths when printed correctly. Unlike some filaments that rely heavily on layer height or additives, ABS forms strong interlayer bonds when kept within its optimal thermal window. This is critical for mechanical parts where forces act across layers rather than along them. When combined with appropriate wall thickness and infill density, ABS components can be remarkably robust.

Infill strategy plays a decisive role. ABS is particularly well-suited to high-infill or even solid prints where strength is paramount. At 100% infill, ABS parts approach isotropic strength characteristics, reducing weak points inherent to additive manufacturing. This does increase material usage and cost, but it also transforms a printed object from a “prototype” into a working component. Professional assessment of load paths and usage conditions ensures material is placed where it matters rather than wasted.

ABS also tolerates post-processing better than most filaments. Acetone vapour smoothing can seal micro-layer gaps, improving surface finish and marginally increasing strength by reducing stress risers. Mechanical finishing—sanding, drilling, tapping—is straightforward due to ABS’s toughness and predictable behaviour. These qualities make ABS especially suitable for parts that must integrate with existing hardware or meet aesthetic expectations.

Economic and Practical Benefits of ABS 3D Printing

From a commercial standpoint, ABS offers exceptional value. The material cost is moderate, machine requirements are well understood, and production workflows are mature. This allows businesses to deliver reliable components without excessive experimentation or risk. For low-volume manufacturing, ABS often eliminates the need for injection moulding entirely, saving thousands in tooling costs and months in lead time.

Replacement parts are a particularly strong use case. Many industries rely on equipment that is no longer supported by original manufacturers. ABS enables direct replication or redesign of discontinued components, restoring functionality at minimal cost. This is not theoretical; it happens regularly in rail, manufacturing, and industrial maintenance environments where downtime is expensive and alternatives are limited.

ABS also supports iterative design. Changes can be implemented rapidly, tested under real conditions, refined, and re-printed without penalty. This agility is something traditional manufacturing cannot match, especially for mechanical parts requiring real-world validation rather than laboratory testing.

Limitations, Trade-Offs, and Informed Material Choice

ABS is not a universal solution, and pretending otherwise does a disservice to clients and engineers alike. Its primary weakness is UV resistance. Prolonged exposure to sunlight will cause ABS to degrade, becoming brittle over time. For outdoor applications, alternatives such as PETG or ASA are often more appropriate. Understanding this limitation is part of responsible material selection.

ABS also emits fumes during printing and requires adequate ventilation. This is manageable in professional environments but should never be ignored. When these considerations are addressed, ABS remains a dependable and highly capable material. It rewards proper process control with performance that few entry-level filaments can match.

FAQs

Is ABS suitable for outdoor use?

It can work short-term, but for long-term UV exposure we usually recommend ASA or another UV-stable option.

Is ABS stronger than PLA?

In many functional situations, yes — especially for impact resistance. PLA can be stiff, but it’s more likely to snap when knocked or stressed.